The Bridge is Love

- There's a land of the living and a land of the dead

- And the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.

- Thorton Wilder

Start the Story

The Trouble with Dying

Robin Reif

Sept 2013

I am face to face with my mother. An urgent call from my sister had me over the bridge from Manhattan to Brooklyn in less than an hour. I meet them in the Flatlands section, where telephone wires stretch high over the streets and the sun sucks the color out of everything. Not tree in sight; a desert of semidetached “Futurama” homes built in the ‘50s. What is my mother doing here? Medicare, I guess, Medicare is what she’s doing here. We’re in her cardiologist's waiting room.

“Mom, why did you take all 5 pills?” I speak softly, trying not to sound accusatory or incredulous. She's downed the full contents of a prescription.

“The doctor said to take it in the morning,” her voice and inflection spookily childlike. She seems bewildered by my shock, a response that only compounds it.

Soon after this incident, we find k-cups scattered across her counters--lids punctured, grounds spilled--as though caffeine-seeking rats had thrown a fiesta. My mother can no longer operate her coffee maker.

moreGlory of the World

Robin Reif

I am dreaming. Dreaming of my body aging: I’m with a group of young women; I ask them to speak up so I can hear. I’m with an old man, hair dyed garish red, who says “people our age. . . ,“ presuming I’m as old as he. I wake thinking sic transit gloria mundi . . . Thus passes the glory of the world, a cautionary line from the old Papal coronation ceremony, a little grandiose as applied to the little old Jewish lady my mother had become, but somehow profoundly apt.

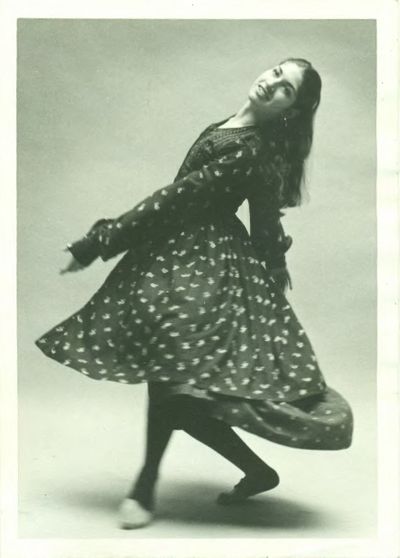

My mother was the glory of the world; of my world, my early world, a world strangely reasserting itself, like the original image on a canvas painted over many times. To my young eyes, she walked in a ring of light wide as the world.

A hazel-eyed, small boned redhead, my mother was striking, smart and “vivaciousness” this last, a highly prized quality in the 50s when Debbie Reynolds was an icon of the popular imagination into which my mother’s was securely plugged. In that post-war burst of mandatory optimism, my mother seemed committed to being perky, even as she popped out enough babies to exhaust and deflate her.

Five offspring into it, she was driving her Rambler, back seat stuffed with toddlers. I remember truckers craning out their windows yelling “Hey, Red,” to get her to look their way. “Men used to stop and stare on the street,” her friend Henny, now 95, told me. “Darling, they weren’t staring at me like that. She was that stunning.”

moreWhere Did She Go?

Robin Reif

After my mother breathed her final breath, where did she go? Being present at her death was to find myself suspended in the profound mystery of things; death, I suppose, the original mystery, that is, after life itself. Even after we wrapped her body, covered her face and stood as she was carried on a pallet from her home, I couldn’t leave, as it was clear to me she hadn’t entirely left.

My sisters, niece and nephew dispersed to other rooms and I sat in a mild stupor on the couch alongside the now empty hospital bed. The atmosphere was strange, the air thinner and lighter. I sat on the couch alongside the now empty hospital bed and, in the stillness, became aware of my body abuzz with activity; I could vaguely sense colonies of living atoms cohering as my solid form. But as my attention extended beyond my body, it was clear that I was not alone.

moreRead the Latest

She Who Gets Slapped

Robin Reif

“Mom, please stop singing.” This, from my 13-year old, as she lies, draped over the couch, head in my lap, half watching, half snoozing through the 2015 Tony Awards. Apparently, I’ve provoked her with my local rendition of You’ll Never Walk Alone, singing along with Josh Groban, who delivers it from the Tony stage.

“Sophie, let Mommy be Mommy!,” my battle cry whenever she tries to restrain my enthusiasms, many of which suddenly became an excruciating embarrassment when she first hit her teens a year ago. She lifts her head, flares her nostrils at me, baring a full mouth of metal before we laugh and she’s down again.

Alas, I feel compelled to sing. I still tear up at Rodgers and Hammerstein’s most exquisite paean to hope. It was my one sadness when cast as the lead in Carousel in Junior High School. A girl with a chest and lung capacity three times the size of mine got to sing it .

On Tony night, the ghosts come out, principally my own: my unlived life as an actress, that lost self who--despite some hard-won fulfillment, evidence of which is in my lap--still harbors a muted version of “I coulda been a contender.” After all these years, the ache’s not gone and I yearn, once more, to shed light on events of long ago; to understand my bloody bang up with the world and with my mother at a fork in the road to which I’ll never return.

moreShe Who Gets Slapped-2

Robin Reif

There’s a theater term, “flop sweat,” which has always made me feel a visceral disgust. It conjures David Mamet characters, ragged with small-time ambition, smelling faintly of fear and alcohol, struggling to succeed on their last chance. I think the term originated in stand up comedy—describing the public humiliation of being up there well into your set and NO ONE is laughing. By 23, I perceived this to be my own reality—I had flop sweat--not for a particular performance but for the performance of my life.

Law School had turned out to be a non- starter and my dream of being an actor, once so vivid, was nearly crushed. If I could have described that dream with the remotest coherence, it might have sounded something like a modern day equivalent of the Moscow Art Theater–an ensemble, a family, a cohort of brilliant people who had something powerful and significant to share with our generation.

I would have talked about the times performing in college or summer stock when I’d slip through a tear in reality and how, once through, time slowed, space enlarged and I WAS Garcia-Lorca’s Yerma or Shakespeare’s Maria or even Fraulein Schneider in Cabaret. In this state, sharing a protected space with fellow actors on stage, there was spontaneity and trust, aliveness and fluency, surprise and adventure. I could be on fire. In the arms of the playwright, I knew the naked truth of my character and of the others so I wasn’t mystified as I so often was in life. My character could be in danger but I never was. I was free to be full-hearted, full-throated, fearless. It was more powerful and pure than anything I’d ever known. To have a life in the theater would be to live a life of meaning.

moreShe Who Gets Slapped-3

Robin Reif

The day before my Yale audition, I took the train to Philadelphia, where the last round of auditions were held, borrowing the dorm room of my mother’s friends’ son, a medical school student named Steve Zamore, someone of the sort I was supposed to marry if all else failed. I got no sleep. Not a second. In an anxious fog, I rehearsed all night like someone praying in prison knowing they’ll be shot in the morning.

The next day, when I walked onto the empty stage, I saw a middle-aged WASP, apparently gay and so bored or hung over, his lids seemed at half-mast. He sat in the 5th or 6th row in semi darkness in a prove-it-to-me slump, and spoke from a distance. I believed he took one look and thought “New York Jew,” sealing my fate before I opened my mouth.

As I began, I focused on the imagined bloody knife in my hand, tried to stay present, to find the space where I could slip into the character and roar my hatred and fear and relief at having killed "my" mother. But fear and fatigue mixed with adrenalin and I was wobbly. I tried to catch the wave but it passed; I swam desperately after it, getting more and more shrill, less and less able to recover. I was awful.

more